BEE BRIEF

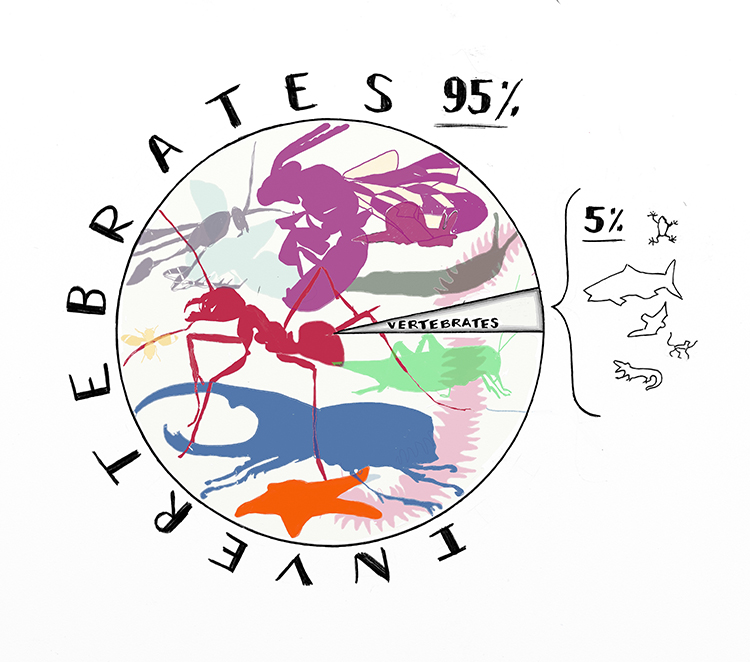

Invertebrates may be spineless, but they run this planet. “All animals in the world are invertebrates,” joked Dr. Susan Masta, associate biology professor at Portland State University whose research lab focuses on processes of biological diversification. “Just some

But the EPA, under the Trump and Obama administrations, has routinely circumvented the pesticide review process. The Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act gives the EPA the authority to allow farmers to temporarily use pesticides too toxic for approval in a crop emergency, like an unexpected blight. In December 2018, right before the country spiraled into a partial government shutdown, the EPA announced “emergency” approvals to spray the insecticide sulfoxaflor on more than 16 million acres of cotton and sorghum, crops which are attractive to bees. The EPA has acknowledged that sulfoxaflor harms bees but is making a so-called emergency exemption across 18 states to control aphids and tarnished plant bugs. According to the EPA, a pile of dead bees near a hive, say from pesticides, doesn’t necessarily mean colony collapse. However, while sulfoxaflor may not kill bees directly, it hampers their reproduction. One study found that a bumblebee queen exposed to sulfoxaflor produced 54 percent fewer male drones and no new queen bees. Bee experts say the pesticides that produce “sublethal stressors,” whether they are neonicotinoid or sulfoximine-based, likely contribute to colony collapse disorder.

Even huge agrochemical corporations like Monsanto, which is steeped in lawsuits over its use of toxic products, acknowledge the importance of insects, namely pollinators. A third of the world’s food production relies on insect pollination. According to the Monsanto-sponsored organization Modern Agriculture, “managed honeybees” are considered the “most valuable pollinators in terms of agricultural economics,” and their estimated market value is at $20 billion. “Honeybees are livestock,” Masta said, because they form colonies. Their eusocial lifestyle makes them viable cargo. But the vast majority of bees are actually solitary. Just because most wild bees don’t form social colonies or make honey doesn’t mean they don’t have pollinating power. “Wild bees,” per Modern Agriculture, have an estimated market value of $4 billion. They’re regarded as “a valuable supplement” to commercial honey bee colonies that even pollinate “certain crops more efficiently than their domesticated counterparts.” But what do we even know about these so-called wild bees?

BEE INSIGHTFUL

Bee populations are in decline, in large part due to habitat loss, agricultural practices, urbanization, and disease. Wild bee populations are diverse. There are about 20,000 species globally, 4,000 species in North America, and over 500 estimated in Oregon alone. But we don’t know much about them. “There is much less known about Northwestern bees,” Masta said. “We’re really centuries behind on the West Coast, just because the systematists [the specialists in taxonomy] didn’t make it out here.”

Despite their ecological value, little research has been conducted into which native bee species occur in the region, let alone the bees’ biology.

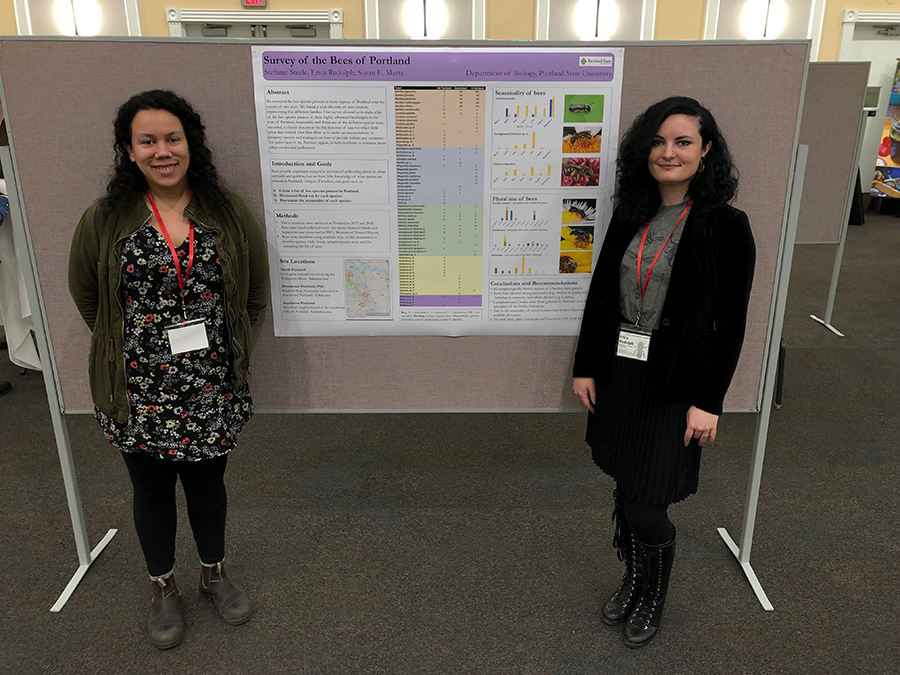

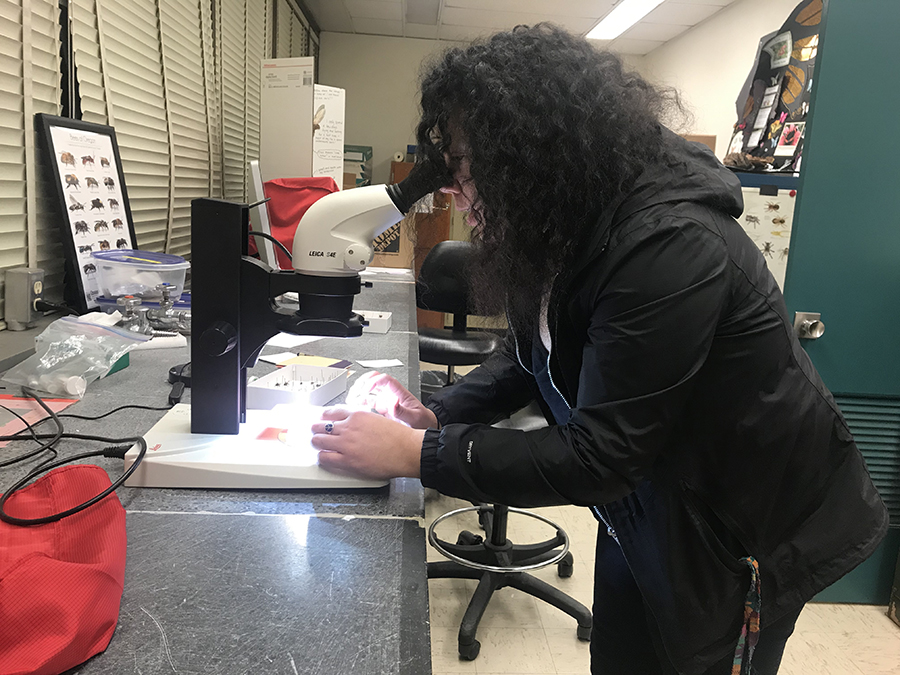

Stefanie Steele is a graduate student in Masta’s lab pioneering research on basic biology about local bees: Who is here? Where do they live? When do they mate? What flowers do they like? “Many bees may be at the risk of extinction,” Steele said. “But we also just don’t know a lot about their life histories, or what habitats or nesting locations they’re occupying.” For the past two years, Steele and undergraduate Erica Rudolph have been working on a comprehensive survey of bees in urban Portland. This study—the first of its kind—indicates that 66 morphologically distinct species can be found throughout the city. Some have yet to be described, but it can be a struggle to identify certain genera of bees if the taxonomic keys don’t even exist. As Masta put it, “Oregon bees just haven’t been studied.”

Steele’s thesis project will research nest preferences within species of cavity-nesting bees. “Most of the bees here are solitary,” Steele said, “most people think of honeybees, which are truly social bees with a true hierarchy system, but these bees are solitary, mostly nesting in the ground, and about 30 percent nesting in cavities, which is what I’ll be focusing on.” Some bee species are multivoltine, meaning they produce multiple generations of offspring in a year, while others are univoltine, having only a single brood a year. “To address the decline it’s important to find where they’re nesting so we can better accommodate them so that they can be successful later.”

Steele says that some of the earliest bees to emerge in spring are cavity-nesters that pollinate fruit trees. They too can be used commercially to pollinate crops like cherry trees and certain apple orchards. Cavity-nesting bees inhabit debris people tend to clear away. “As a society, we have a pressure to tidy our yards and remove all these imperfections and make things look nice to us, but we’re really removing important habitat for these bees as well as other organisms.” Old logs riddled with beetle bore holes, fallen branches, and pithy plant stems might be unseemly to us, but for some native bees, they’re home sweet home. More people are buying supplemental nests, but the models could be better if based on research. For example, people are advised to place their supplemental bee nests at eye level. “From my understanding,” Steele said, “that is for our pleasure—to be able to view them,” but there may be a better way to set the native bees up for success.

Steele will focus primarily on preferred nesting heights of each species of cavity-nesting bees in the Portland area. The results of the study will also provide insight into which bee species are inhabiting the cavities, the nest features, and differences in bee diversity. The survey already established that some places house more diversity than others, while some places appear to attract certain house-hunters. An ecological restoration site in an industrial area of North Portland, for example, had the most cavity-nesting bees. Steele thinks bees may be flying over the river from Forest Park because the site offers a lot of good real estate: driftwood logs from the Willamette River line the educational garden there and are perfect homes for cavity-nesting bees.

This spring, Steele will place nest boxes in at least ten sites throughout Portland, mostly in residential gardens across the city, as well as in a large industrial educational garden in North Portland, a farm in Oregon City, and on the PSU campus. The nest boxes are designed with features known to improve nesting success. For example, they offer a range of nesting holes to accommodate the range of bee sizes. The boxes will be collected in fall, put in a cooler for diapause, and then warmed up until the adult bees emerge. Diapause is a developmental phase of dormancy similar to hibernation. Steele is also the first to establish a procedure for shortening the duration of diapause for native bees, as a way to study who exactly emerges in a more timely fashion.

Based on data from Survey of the Bees of Portland, Steele’s thesis will focus on three out of the total five families of bees that live in North America: Megachilidae, Apidae, and Colletidae. She anticipates finding kleptoparasitic bees too. “They’re a good bioindicator—a good sign—because it means the bees that they rely on are around too.”

Parasitoid wasps are also part of the picture. If the cavities are good for cavity-nesting bees, they are good for cavity-nesting wasps too. But their presence isn’t “bad” per se, they are just a natural part of bee-life. But not to worry—according to Rudolph, who is also a wasp-enthusiast in Masta’s Lab, “The wasps are also really important, and they’re not super mean! They’re mostly solitary and don’t really sting.” You don’t need to love bugs to appreciate the work Masta’s lab is doing, but you may want to give them a second thought, a closer look, and at very least, a safe home in some cozy dead wood.

Kleptoparasitic bees: parasitize by stealing (as the name suggests, they are kleptos). They survive by laying their eggs in other bees’ nests; when the parasitic bees emerge, they kill and steal resources from the host bees’ brood.

Diapause: developmental stage of dormancy similar to hibernation that a species uses to avoid adverse environmental conditions.

Multivoltine: multiple generations of offspring occur within a year, typically adult populations don’t live very long after mating.

Univoltine: one single generation of offspring occurring in a year.