You may have glimpsed it from the corner of your eye, a blur of white movement along the sidewalk as you walk to class. You may not even remember the encounter, its quick movements relegated to the depths of your subconscious. It has admirers by the hundreds, strangers who walk among you, unknowingly united by a single creature. It is a pigeon unlike the rest.

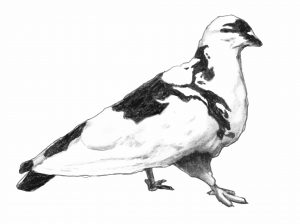

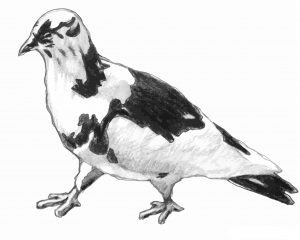

Dubbed “Little Cow Pigeon” due to its distinct white plumage with large black spots, reminiscent of a stereotypical dairy cow, the unique bird can be regularly spotted on the campus at Portland State University. The Urban Plaza, Karl Miller Center, and PSU’s Park Blocks are all frequent Cow Pigeon hangout spots.

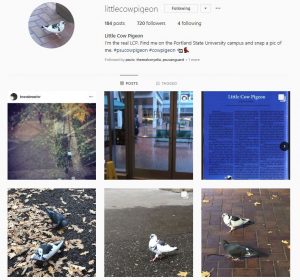

Cow Pigeon’s ascent to public figure status began in November 2017, when the @littlecowpigeon Instagram account was created. Flyers began appearing around campus, reading “Have You Seen This Bird?” and directing viewers to Instagram.

“I suppose the first mention of Little Cow Pigeon came about summer of 2017 when a few of us studying at PSU brought up this pigeon we saw on campus often randomly, that was strikingly black and white,” said the account’s creator, who wished to stay anonymous. “For some reason we all knew this pigeon and coined it the Cow Pigeon.”

It’s a similar story for many fans of the account. Exclamations of “that does sound familiar” or “I was just thinking of that bird last week!” are common when introducing the uninitiated to Cow Pigeon. Curious interest gradually becomes an emotional connection with the bird as users follow its antics online. When Cow Pigeon developed a limp last spring, many followers expressed concern for its well-being and collectively sighed relief when the limp passed.

The account’s creator, a PSU film major who graduated last year, assumed the account would come to an end when they moved out of state after graduating. But “LCP,” as many followers lovingly refer to the bird, “has gained enough attention that the PSU community sends in content on the regular keeping the account alive and active even from a distance,” they said. “I created this account to see if anyone else at PSU had an encounter and cared, and people did, crazy huh?”

“Following Cow Pigeon on Instagram and in real life has gotten me interested in the pigeon behavior patterns that I’ve overlooked for so many years,” said PSU student Alejandro Matias. “Darwin would be proud,” he joked.

I spoke to Dr. Michael T. Murphy, a professor of biology at PSU who specializes in working with birds, to find out more about Little Cow Pigeon. An ecologist by training, his experience with birds entails about 40 years of field research on a variety of different species, principally Eastern Kingbirds, as well as his position as curator of birds at Portland State’s Museum of Natural History.

Murphy confirmed that the striking black-and-white bird is specifically a Rock Pigeon, a common species with an incredibly wide distribution across the world. Introduced to North America by humans in the early 1600s, it has been extremely successful, with estimates of tens of millions of Rock Pigeons in the United States and Canada alone.

According to Murphy, seeing Cow Pigeon frequenting certain spots on campus is not uncommon. “They have a fairly well prescribed area that they’re going to live within, and they’ve got stable social relationships,” he said. “Males and females will pair up and they will stay together for long periods of time.” Rock Pigeons have the potential to breed year-round, usually hatching two eggs at a time and will reuse a nest for many offspring.

However, there is no clear way of knowing Cow Pigeon’s sex without getting a closer look. We can’t tell externally whether it’s male or female unless we had it in hand,” Murphy explained. “Testes are internal in birds, and there is no penis. And the plumages are similar to identical. If we knew where the bird was nesting we could check incubation patterns; males typically incubate during the day and females at night—but it may not even be breeding right now.”

“Despite the fact they are so common, there’s still a lot we don’t know about their actual behavior, because it’s an introduced species, and people don’t pay a whole lot of attention,” he said. “It’s not found out in the wild [in the United States], it’s not threatened, it’s living amongst us, but we walk around them all day long and we don’t really pay all that much attention to them—unless they look a little odd.”

As for Cow Pigeon’s certainly odd coat, Murphy was fortunately able to provide a fascinating, and complicated, explanation.

“As it turns out, these pigeons have been the subject of a lot of study about the genetics of coloration,” he said. “We probably know more about that in these guys than any other bird species, and it’s because we can bring them into the lab, we can breed them, and they’re really cooperative around people. Geneticists back by the 1920s–30s had actually worked out a lot of the basis for this color pattern. And what it turns out to be is, there’s several complicating factors.”

Murphy explained there are several factors that go into creating Cow Pigeon’s plumage. Rock Pigeons have separate genes on separate chromosomes for both color variation and pattern variation. The color gene has three different forms, called alleles. It is also sex-linked in such a way that females only get one copy of the gene, but males have two, resulting in dominant and recessive alleles in the latter sex. Males can exhibit a lot of variation in color, but females will likely show more variation, because they’ve only got one allele and they’re always going to express it.

A Rock Pigeon’s pattern—how the colors are expressed over the body—is determined by an unrelated gene, on a non-sex-linked chromosome. The pattern allele has six different variations.

“Now you’ve got two different genes, three different color possibilities, six different pattern possibilities, and when you bring that all together, you get this potential to create an incredibly variable set of plumages.” But all these genetic factors still don’t add up to create Cow Pigeon quite yet.

“On top of all that, the white that you see there is actually the result of the failure of pigment cells to be put down in the skin,” Murphy noted. That doesn’t mean Cow Pigeon is an albino, but rather a leucistic bird. This occurs when certain pigment cells called melanocytes are not deposited while it is developing as an embryo. If it were a true albino, its eyes and feet would not have pigments in them. “So this guy, on top of all of that chromosomal stuff and different copies of genes—boom—a failure to develop properly. It didn’t get the pigment cells laid down where it should’ve been.” All this conspires to produce an exceptionally rare bird.

Murphy thought it was worth noting further that such a variety of coloration is also the result of humans selecting for these different color patterns in various ways. “The diversity is there but it’s not normally expressed in nature. But when we get them under our human-dominated conditions where we have these feral populations, the different varieties that humans have selected over the years are able to emerge.”

In Regions with truly wild Rock Pigeon colonies, they don’t show this same range of variation in one single population. “As it turns out, with their wide geographic distribution, if you move from a southern location along the Mediterranean and northward into higher and higher latitudes, coloration gets darker. So they do exhibit that kind of variation, but these multiple different color patterns is quite unusual for wild birds.”

Murphy noted that in nature, a bird like this would be even rarer and probably not survive long, as it would attract a predator’s attention more easily by sticking out from the rest of its kind. Even at PSU, Cow Pigeon isn’t going to be around forever. Once Rock Pigeons reach adulthood, there’s “a 65 percent chance of survival from one year to the next, so that means if you had a population of 100, after about five years, there’d only be about 11 out of 100 surviving, on average, so most of them aren’t going to live more than four or five years.”

“Given the world they live in, they do quite well, and they couldn’t be stupid animals to be doing so well. They can learn quite a bit, and they certainly can learn that humans can be trained to feed them.” Murphy emphasized that while we may view them simply as stupid pigeons, they’re far from it. “Behaviorists have studied [Rock Pigeons] and they exhibit some behaviors in standard trials which actually indicate they’re probably a little more intelligent than cats.”

And perhaps Darwin really would be proud of Cow Pigeon’s notoriety. Rock pigeons were instrumental in influencing Charles Darwin in his understanding of how selection could work. “He did breed them to produce different varieties, and it helped him to formulate the notions of how different varieties could appear and then come to dominate in the population.”

Towards the end of our discussion, Murphy had a message for Cow Pigeon’s followers. “Kudos to those folks who saw this specific bird and paid attention but realize the other birds around there are worthy of your observation too,” Murphy said. “We take them for granted most of the time, but this particular species has contributed a whole lot to science and our understanding of the world. From how natural selection works, to how organisms navigate using magnetic fields, to how we learn [about genetics], they really contributed considerably. We kind of find them a pain in the neck sometimes, but that’s pretty cool.”

“I think the big message might be, life is all around you. Even though we live in an urban environment and we exclude a lot of the creatures that would otherwise be here, there’s still a lot of life here worthy of our attention.” The so-called Little Cow Pigeon just happens to be one very noticeable example.