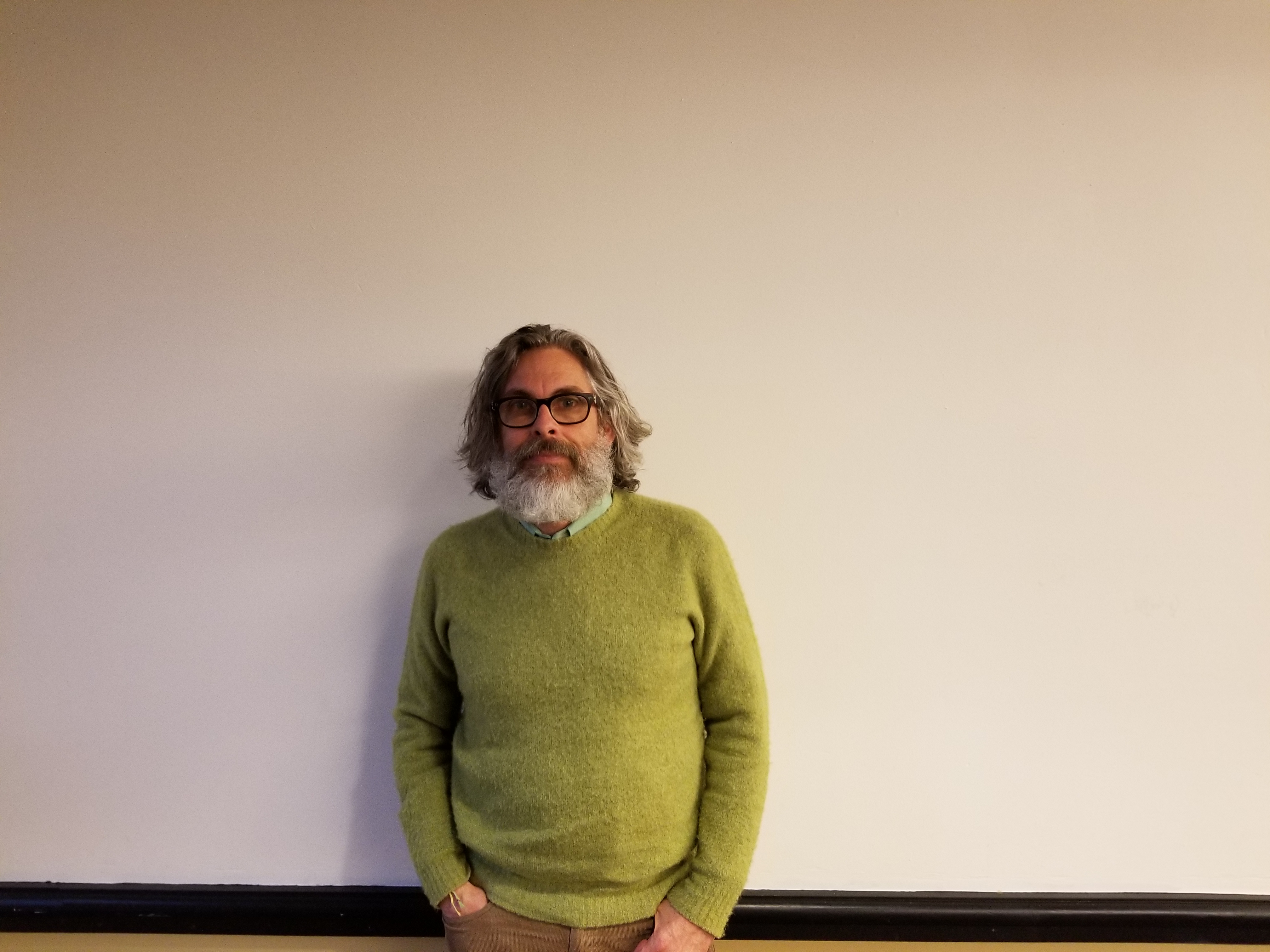

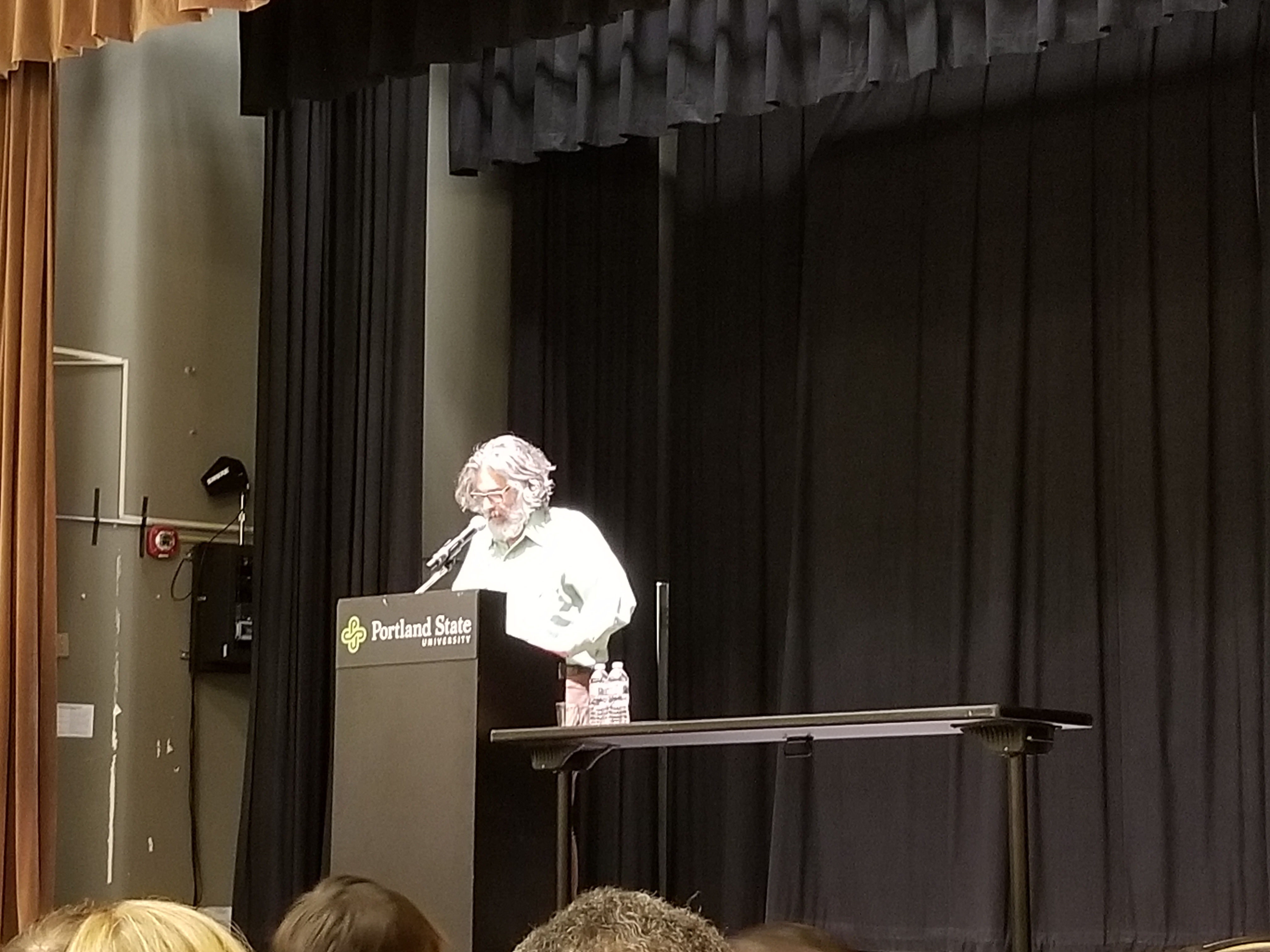

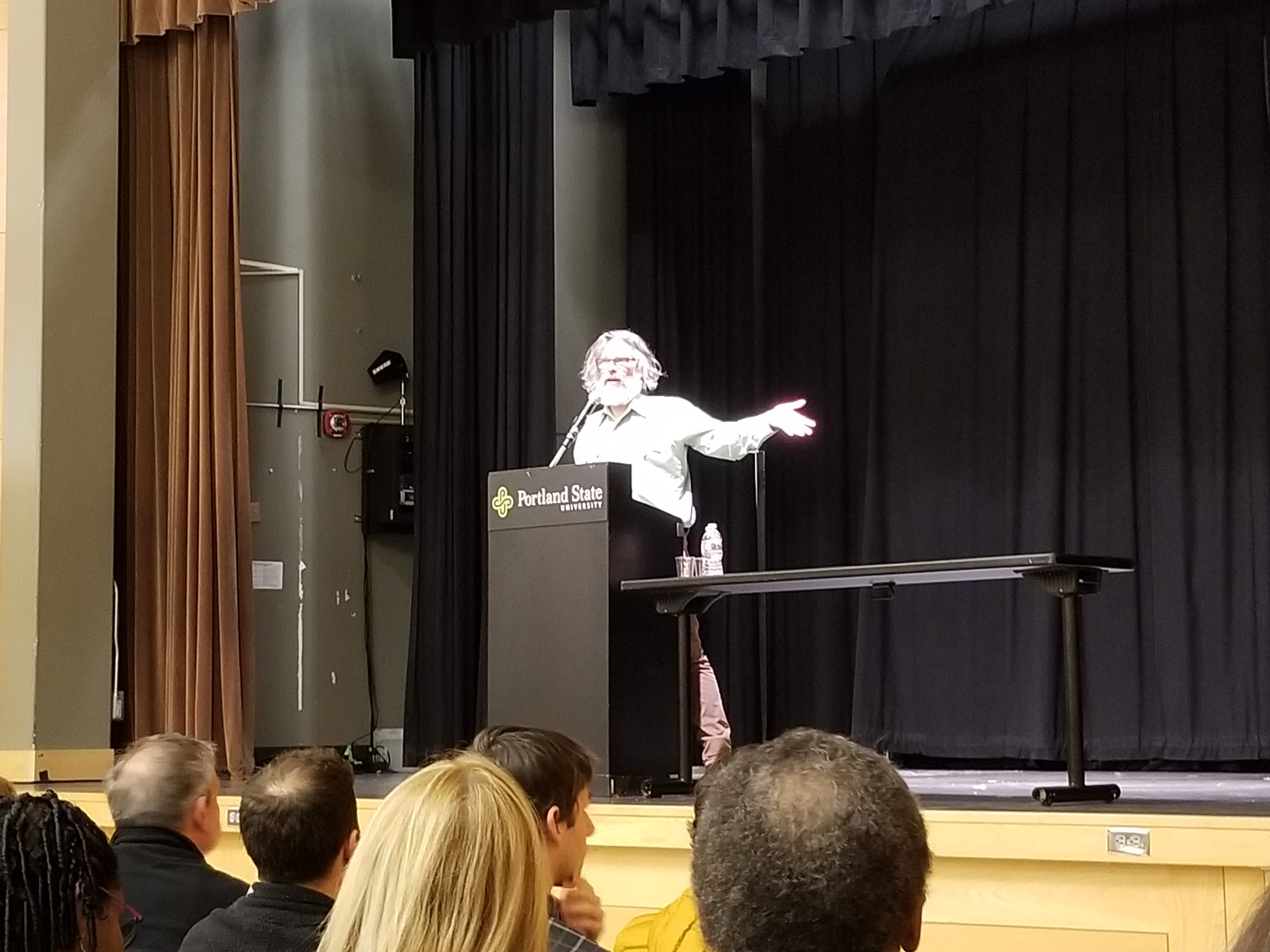

Meet Michael Chabon, who came to campus on the 27th of January to speak at an Honors College Event. Before we continue, allow me, on behalf of the author, to instruct you in the proper pronunciation of his surname: it’s shay-bon— like Shea Stadium and bon like Bon Jovi. Chabon has won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction (for The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay in 2001), the Hugo and Nebula Awards for Best Novel (for The Yiddish Policemen’s Union in 2008), and numerous other accolades and notices. In addition to his career as a man of letters, Chabon has personal connections to Portland State University and to our fair city of rivers: his step-mother Shelly Chabon is Vice Provost for Academic Personnel and Dean of Interdisciplinary General Education, and the family of his first wife, Lollie Groth, are from Portland. “I got to know Portland at the tail end before it became New Portland,” he said of his recollections of the city.

On that Monday afternoon in late January, Chabon met with about a dozen students from the Honors College and the creative writing MFA. When he arrived and saw that students had seated themselves as if for formal presentation, the author asked them to form a circle to conduct a conversation. “You can ask me anything,” Chabon said. “It doesn’t have to be about writing. It can be about relationships and dating. It can be financial advice, but it will be bad.”

One attendee, who said he was “just starting out” in a fiction MFA, asked Chabon about MFA programs in fiction. “I want to be open,” the attendee said of the program, ”but I’m also a little resistant.”

“Well, that’s probably smart,” Chabon responded, adding that the circumstances of his own MFA experience were such that it would have been easy for him to make it an “unhappy and unfortunate” time. Chabon entered the two-year MFA program at University of California, Irvine in the autumn of 1985. At that time, the only full-time faculty for the writing program were Oakley Hall (known for the novel Warlock, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer in 1958) and MacDonald Harris (nom de plume of Donald Heiney), “so there wasn’t a whole lot of range to try to find a mentor,” Chabon said. Each cohort comprised six students, for a total of twelve in the program at a time. “When I started there, I was writing what I saw as science fiction, fantasy-tinged writing that also had aspirations to literature,” he said, citing Ursula K. Le Guin, Italo Calvino, and JG Ballard as models for how such an approach could be successful and taken seriously. According to Chabon, the instructors as well as the students in the workshops (the peer critique format standard to most creative writing courses) responded as though science fiction didn’t depend on the quality of prose style, the depth of characterization, the use of metaphor and imagery—“all the things that one expects to find in serious literary fiction.” When Chabon brought stories of this kind to the workshops, he said that both instructors (“one more than the other”) and all his fellow students said, in response: “I don’t like science fiction, I don’t read science fiction, I don’t understand science fiction—so I can’t help.

“At that point, I could have made the worst of it,” Chabon said, by either turning the duration of the graduate program into a confrontation or by giving up. “Instead, I decided to do what I do best,” he said, ”which is to accommodate and adjust,” a trait he attributes to growing up amidst his parents’ divorce. “So I decided not to fight and to take advantage and make the most of my fellow [MFA] candidates, who were really smart, except for this one blind spot, and to make the most of my two professors.” Chabon’s MFA thesis project ultimately became his first novel, Mysteries of Pittsburgh, which he characterizes as “very much a mainstream novel” in contrast with the science-fiction inflected literature that most engaged his imagination, and continues to be an element in his work thirty years later.

photographs by Van Vanderwall

photographs by Van Vanderwall

To conclude the answer to the initial question about MFA programs, Chabon said that “it’s easy to be derailed” by the opinions and critiques of one’s fellow MFA students. He urges people in such programs to “find a middle ground” between “being derailed and being able to take advantage of the resources around you.”

Another attendee, named Emma, asked about Chabon’s writing process and what it looks like as part of a daily routine. “I used to say that I wrote five days a week, but now I actually write every day—and I work at night,” Chabon said. “At Irvine, when I was in graduate school, I discovered that I liked to write at night” because “that’s when it feels quietest,” which he says was especially true of his time in graduate school in the mid-eighties “when there was no internet and nothing happening,” whereas “now, unfortunately, there’s always something happening, even at three o’clock in the morning.” He goes on to say that night work, and his facility for writing then, is still his preferred mode, although the distractions of the internet can sometimes interfere, but to a lesser extent than during the day when, for example, people are still sending emails. “I like to work from 10 p.m. until three or four in the morning,” he said. “If I’m on deadline, I’ll just stay up until five or six in the morning.”

When he was writing scripts for the first season of Star Trek: Picard last spring into the fall, on at least a few occasions he stayed up for twenty-four hours or more, writing continuously. At the beginning of that project, Chabon was using “a fairly large laptop” that was his only computer. During writing and preproduction for Star Trek: Picard, when he frequently flew between his home in Berkeley and the production in Los Angeles, he began using a “smaller Macbook;” within four months the “a-, s-, and f-keys were totally worn out,” which elicited laughter from the group. During that period, when his typical night-shift routine was impossible, he wrote “whenever, any time of day” because the routine was that of being in production and having to provide lines for the actors to say—“otherwise it would get kind of quiet.”

When not involved in such production schedules, and abiding by his nocturnal writing practice, he finds that he gets “a page or so” in the first hour or two of writing, after which his pace accelerates. “I try to get a thousand words,” he said of his daily quota, a goal that includes rewrites and revisions. “Sometimes I have to strain to get my one thousand words.” And yet, books are long. “The only way you get to the end of them is to add a thousand words at a time. By the end [of a project], I’m inspired by finishing.”

“Inspiration is like grace—it’s unmerited, unlooked for, and undeserved.” —Michael Chabon

A high-school teacher asked Chabon what he would think about having his novels adapted into films. “Actually, two of my books have been filmed,” Chabon responded, going on to call himself “very much an observer of the process” by which his second novel Wonder Boys was adapted for film by screenwriter Steve Kloves (renowned at the time for the script of The Fabulous Baker Boys, and later for screenwriting credits on all but one of the Harry Potter films) and director Curtis Hanson (who also directed LA Confidential and 8 Mile). His first novel, Mysteries of Pittsburgh, was later adapted into a film of the same name “to much less financial success. Even though Wonder Boys [the film] wasn’t especially successful either, Mysteries of Pittsburgh kind of vanished.” The latter film, which was released in 2008, was written and directed by “a guy named Rawson Thurber, who, at that point, was known only for having written and directed a movie called DodgeBall” (a comment that made the attendees laugh). “He loved the book and he talked me into it,” Chabon said. “He did his best, but he had no budget, and it [the film] just didn’t work very well.” Chabon continued: “So I’ve had both of the possible kinds of experiences. Wonder Boys came out great, it’s a really good movie, it stands very much on its own two feet, and it does some things better than the book did them.” He expressed admiration for the acting and Hanson’s directing, and he digressed from discussing Wonder Boys the film to expound on the merits of Curtis Hanson as “a really underrated great director” who died “without having gotten the level of acclaim of other directors of his generation.” Chabon characterizes the artistic success of Wonder Boys the film as “a great experience.”

To explain the supposed tension between authors and the creative teams for film adaptations, between books and movies, Chabon told a (possibly apocryphal) story about James Cain, author of Double Indemnity, The Postman Always Rings Twice, and numerous other books, many of which have been filmed (some more than once).

An interviewer asked Cain, “How do you feel about what Hollywood has done to your books?”

“They haven’t done anything to my books—they’re right over there,” Cain said, gesturing to a bookshelf containing his published works.

Chabon commented on the story, saying, “For most writers, for most books, that’s true. Some movies supplant the books they’re based on to some degree.” He cites Endless Love by Scott Spencer, “which was turned into a terrible movie” that was so widely reviled as to subsume any merit that the book had as “a really dark novel of sexual obsession.” This is, in Chabon’s estimation, one of the few examples of a book that was “destroyed” by a bad film adaptation. Because of the independence of film and book versions, Chabon considers it disingenuous when authors claim that film adaptations have ruined their books; authors elect to sell film rights, so if they don’t want film adaptations they need not permit the sale.

An attendee named Josh asked about the process of sending Mysteries of Pittsburgh to publishers and dealing with rejection, and, perhaps most of all, how to decide what to send to publishers for consideration. “I’m a really poor object lesson in perseverance,” Chabon said. The summer before enrolling at Irvine for his MFA, Chabon visited the program, where he noticed that nobody wrote science fiction (leading him to initially adopt a combative stance before later deciding to “make the best of it”), and, furthermore, everyone seemed to be working on a novel; this latter observation turned out to be false, a result of mishearing people describe their projects, but it nonetheless spurred Chabon to direct his efforts toward a novel. As he recalls (allowing that this is likely not quite how events truly occurred), he returned from the trip and went to the daylight basement room in his mother and stepfather’s house and sat on the bed, feeling overwhelmed by the task of writing a novel. As he looked at the bookcases in front of him, filled with many of his stepfather’s books from his own college days, his eye alighted on The Great Gatsby. Chabon had read the novel in college (not for class, but on a friend’s recommendation), which “didn’t make much of an impression on [him] one way or the other.” This time, however, he pulled it off the shelf and read it in one sitting on the day he had returned home. “I loved it and it made a huge impression on me. It had this retrospective voice of Nick Carraway looking back on that summer. Somehow that retrospective of looking back on a time when things were more vivid said something to me.” So he put Gatsby back on the shelf, and noticed that adjacent to it was Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus. “Right away I realized that Philip Roth had read The Great Gatsby,” that “The Great Gatsby had inspired a lot of what’s in Goodbye, Columbus.” Like The Great Gatsby, Goodbye, Columbus takes place over a summer, is also retrospective, and is also about what seems, to a young man, to have been “a more vivid time period.”

“So I thought, ‘That must be how you write a novel. I’ll just write a novel that takes place over the summer,’” he said of his conclusion after reading the two books. He decided to try to capture the “wistful” and “sardonic” narrative voice that evokes “a vanished moment in life;” the summer timeline also fell into “a natural three-act structure” of June, July, and August. When he brought an early draft of a part of the novel to workshop at Irvine, MacDonald Harris said, “It’s obvious that Michael knows what he’s doing here; all we can do is derail him. The best thing to do is to leave him alone.” Chabon said, “I was really happy to hear that, but my fellow MFA students were a little dismayed by that.” Tensions increased over the course of the two-year program, with Chabon, in his telling, enjoying a uniquely exalted status in the eyes of Professors Harris and Hall. At the end of the second year, when Chabon submitted to Harris a completed draft of Mysteries of Pittsburgh as his thesis project, the latter, on behalf of his student, subsequently submitted the manuscript to his agent in New York without informing Chabon.

The following week, Chabon attended the final workshop in the MFA program, during which his peers savaged his work. He recalls thinking, “Well, you might be right, but an agent has that.” The agency ultimately offered Chabon an advance about twenty times what most first-time novelists receive. Because he did not have to engage in the scrum, the scramble, and the hustle to break into publishing, he didn’t yet know how to take himself seriously and it took him “a long time to catch up.” For years he grappled with the project meant to be his second novel, Fountain City, before ultimately abandoning it, partly because of this uncertainty: “I didn’t know what kind of novelist I was trying to be.” He had initially set out to write “fabulous science fiction” in the vein of Italo Calvino, whereas Mysteries was a “bisexual coming-of-age story set in Pittsburgh”—not the novel he had ever intended to write, but one that he worried would define what others would expect from him.

Misgivings and doubts aside, Chabon said, “There was only ever one thing I wanted to do, and only one thing I was any good at. Fortunately for me those two are identical.”

Another student in attendance asked Chabon about the experience of getting an idea for a creative project, only to discover that a similar work already exists. The student asked what to do when this occurs. Chabon responded that this has happened to him three times, each time in a more dramatic, less easily-ignored way. “When I was writing The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, this book came out called Derby Dugan’s Depression Funnies by Tom De Haven, who’s a pretty good writer.” Chabon obtained an advance reading copy of the Derby Dugan novel a few months before its release. De Haven’s book was set in 1920s New York, centered on newspaper comic strip artists; Chabon’s was about comic book artists in New York in the 1930s. The similarity between the two conceits surprised Chabon, who “thought [he] had the territory to himself,” insofar as he had never seen any such books and found that when he told people about his project, “they thought it was a terrible idea.” The attendees laughed at this memory. “I’m safe because nobody else would want to write this book,” Chabon said. When he “riffled through pages” of Derby Dugan and “glanced through it,” he realized that De Haven’s book “wasn’t at all the kind of thing I was trying to do.” He decided that one or the other book could flop, which led to his next decision. “I decided to ignore it. I came into this life ill-equipped in a lot of ways, but I was gifted with amazing powers of denial.” Two authors had independently hit upon similar concepts at the same time, but no harm came of it. Ultimately Chabon’s novel won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 2001. (“It was a wonderful day and it will probably never happen again—and that’s ok,” he said as he recollected the day he received news of the award.)

About a year later, Chabon again experienced the phenomenon of simultaneous, independent creation of similar works. “Then when I was writing Summerland, I got the advance reading copy of a book, by my friend Neil Gaiman, called American Gods.” Both books are about mythologies from around the world playing out in America and merging with Native American mythology and contemporary American pop culture; in Chabon’s book, the focus is on baseball, whereas roadside attractions and cons and scams occupy the foreground in American Gods. Again, Chabon read through an advance copy to ascertain how similar the novels were. “This [American Gods] is for adults; I’m writing for children. This doesn’t appear to have any baseball in it. I could just feel that he was trying to do something different from what I was trying to do. And, again, I have magical powers of denial.”

The third instance of this simultaneous similarity phenomenon concerned the most prominent author yet. “It happened again when I was writing Yiddish Policemen’s Union, this Jewish alternate history. I got the advance reading copy of Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America,” which is a Jewish counterfactual history that imagines what would have happened had Charles Lindbergh won the presidency on an isolationist, anti-Semitic platform. “I just went through the same process: I found things to reassure myself that it [The Plot Against America] was different enough [from Yiddish Policemen’s Union] that it didn’t matter.”

“I’m just trying to write books that I would want to read.” —Michael Chabon

Chabon then returned to addressing the student’s question about the appropriate course of action for ideas that one discovers to be similar to, but not copies of, the works of others. “You are absolutely required to do something different with similar material, or even the same material,” Chabon said. “You can comfort and console yourself with two things. One is that there’s nothing new; at this point in history, it’s all variations on themes. There are only so many themes, and in the variation is your possibility. You can’t worry that you’re writing about the same basic elements as even a really well-known and popular book. In fact, I think you should revel in that and find ways to make allusions to that other work…to be in dialogue with it.”

The second piece of comfort is this: “Even if you tried as hard as you possibly could to copy the thing, you would fail.” No two artists are identical: each has his or her own strengths, weaknesses, interests, foibles, etc., so no work will be a trite rehash if one honestly endeavors to create something new. “Even if you decided to write a novel about little creatures going to drop a ring of power into a volcano” it would not be a knock-off. Consider Chabon’s tale of the origin of The Mysteries of Pittsburgh as revisiting The Great Gatsby and Goodbye, Columbus (the latter of which was itself an homage to the former).

Indeed, as Chabon’s experience illustrates, there is sometimes a zeitgeist for particular ideas. Consider how two movies released in 2006, The Illusionist and The Prestige, are about the feuds of late-nineteenth-century stage magicians. Red Planet and Mission to Mars, which came out in 2000, are about manned expeditions to Mars that discover extraterrestrial life. There are also the numerous television westerns popular in the 1950s and 1960s, natural disaster movies of the 1990s and early 2000s. To expand on what Chabon asserted about the finite number of available themes, some themes seem to crop up in seasons or to somehow simultaneously suggest themselves to independent creators, which Elizabeth Gilbert writes about in Big Magic.

After the group discussion, I asked Chabon about the authors who most inspire him now. In addition to Louis Hynde and Zadie Smith, writers roughly a part of Chabon’s generation, he frequently rereads F. Scott Fitzgerald, Raymond Chandler, John Cheever, Eudora Welty, James Joyce, and Vladimir Nabokov. These authors inspired him in his youth and continue to do so; he described his reading selections as circumscribed, the better to protect the sensibility he has worked so long to cultivate by imbibing the words of his literary models.

The discussion covered yet more material than this, but much of it can be distilled down to a few simple ideas: read a lot of good books (and be protective of what is taken into the mind), keep a steady writing practice (because it’s a craft, not a series of miracles), abide by principles (aesthetic and ethical, and perhaps religious as well), be bold, and keep going. That’s how the great ones do it, that’s how Chabon does it. And that’s how it’s done.